For nearly two months, Kendrick Harrelson never left the fire restoration company where he worked. Literally.

At night, he went into a back storage room, inflated an old air mattress and tried falling asleep while a small pinprick hole left his bed slowly sinking to the floor.

“Being homeless as a veteran, it’s a rough ordeal,” Harrelson said. “It was depressing. I really could have let myself go.”

These days, the sleep comes easily.

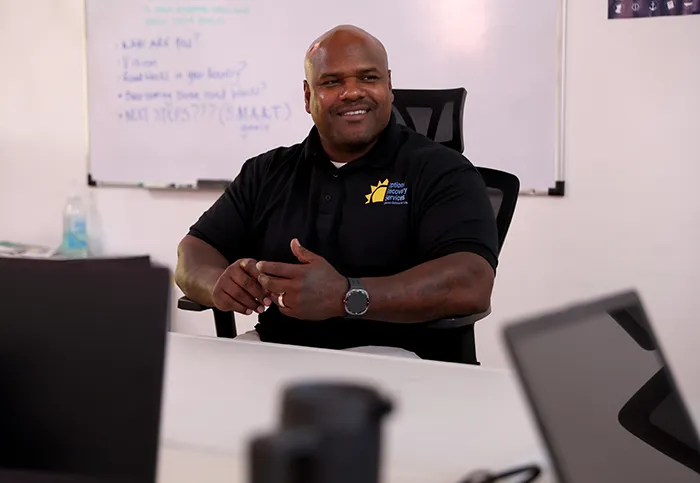

A college student at 49 and living in a house with his girlfriend, Harrelson ranks among a small-but-growing number of military veterans to graduate from the Veterans Accession House. The nonprofit operates a duplex in Pittsburg where veterans can come in from the streets, get jobs and find stability while looking for a place of their own.

For Harrelson, the organization helped him climb out of homelessness and, more recently, win the right to once again visit his 9-year-old daughter.

“I was given a second chance, and I’m very blessed and grateful for that,” Harrelson said.

Veterans Accession House received funding this year from Share the Spirit, an annual holiday campaign that serves residents in need in the East Bay. Donations will help support 56 nonprofit agencies in Contra Costa and Alameda counties. The nonprofit plans to use its grant to install an air conditioning unit in one home and improve ventilation in another.

The program operates on the notion that veterans know what’s best for their former comrades in arms, including how to avoid homelessness.

It began about five years ago, when Leonard Ramirez sought a way to give back after a life spent in the military and law enforcement. An Army reservist while working at the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department, he deployed twice to Iraq, once to Afghanistan and also to the Balkans.

At first, he purchased the Pittsburg house with the plan of simply renting it out.

But as he walked through it, he “kind of got a vibe for it.” In that moment, he decided to turn it into transitional housing and join other nonprofits in the fight against veteran homelessness.

“While everyone’s doing a great job, there’s only so much capacity in all these different programs,” Ramirez said. “We’re kind of like a safety net for the safety nets.”

A case manager at another nonprofit mentioned the need for one person in particular — a homeless man living in a park in Concord — to find a bed, and Ramirez welcomed him indoors. From then on, word spread on the street of a new place for homeless veterans to get indoors, and the duplex filled up.

For the first few years, Ramirez did all of it on his own dime.

“To me, I guess it was a calling,” Ramirez said. “It’s not a feel-good thing. It’s a duty.”

Homelessness among veterans remains a dire issue across the Bay Area. The most recent Point in Time survey, conducted in 2019, found 361 homeless military veterans living across Oakland — nearly all of whom were living unsheltered in tents, cars or on the streets.

Another 476 homeless veterans were found in San Jose — three out of every five of them living unsheltered.

Ramirez’s program caters both to people who are currently homeless, as well as those who are at risk hitting the streets. They are encouraged to attend college or vocational training, and must be sober. Instead of rent, they pay a “program service fee” that is adjusted to their income and never tops $400 a month, Ramirez said.

Walking up the front steps, tenants find a warm living room with an ornamental fireplace, a full kitchen and computers to apply for jobs or do school work. They often sleep two to a room.

Sitting in his bedroom, Nels Rasmussen recalled spending about four months being homeless — crashing on friends’ couches and at various motels. But since moving into Ramirez’s house, Rasmussen has enrolled at Berkeley City College and his finances are stabilizing.

Case managers, which frequently visit the house, also are helping him seek improved benefits through the Department of Veterans Affairs.

“There’s a lot of empowerment that’s been going on here,” Rasmussen said. “It’s turning into quite a community.”

A graduate of the same program, Harrelson agrees.

He had been homeless twice before arriving at the Pittsburg house — once more than five years ago while battling an addiction to methamphetamine, and again about three years ago when business slumped at his job restoring fire-damaged properties.

Reluctant to check into a shelter, Harrelson worked out a deal with his boss to allow him to sleep at his workplace. There he went to bed every night in a storage room on an air mattress that deflated every night.

“It wasn’t the most comfortable place to sleep — it was a place of business,” Harrelson said.

He learned of the Veterans Accession House from a friend and jumped at the opportunity.

He stayed there two years and ultimately enrolled at Intercoast College, where he is studying to become a heating and air conditioning repairman. Most critically, he received a 100% disability rating from the VA, meaning heftier monthly benefits from the agency.

He now lives in Sacramento with his girlfriend — a life he never would have known without Ramirez.

“To be able to overcome adversity with the help of the Veterans Accession House, I was able to turn my life around,” Harrelson said. “I got my children back in my life again. It’s a great feeling. I’m very proud of myself.”